Positive punishment and prancing prairie dogs

Dog training nuance and sharing space with Montana's wild creatures

Right now, Montana is red rocks and crumbly terrain and a few haphazard plants doing their best to keep roots in the loose soil. When I texted a photo of the big sky at our dispersed campsite to my dad, he replied “but no trees”. (He was wrong. There was one tree. We saw the northern lights through its branches before bed.)

Scout looks good in a place like this. I love the pale sun on her fur, flecks of dust reflecting the rays; her soft squinty eyes; the stark contrast of her graying-but-still-black ears against the lake on the horizon. She looks good here, and she feels good here. She has seemed strong since we drove into this deserted recreation area past hundreds of prairie dogs and dozens of cows and a single burrowing owl.

Ah, the prairie dogs. They’ve been some of my favorite small creatures since a childhood vacation to South Dakota with my family. At two—my first road trip—I cried because I wasn’t allowed to bring one home. At 26—our first year living in Hermes the yellow van—Sean and I sat on the ground in Theodore Roosevelt National Park and watched the prairie dogs forget we were there. (They do this amazing thing called a “jump-yip” when they’re comfortable: They leap like gymnasts, or perhaps junior high students taking a self-timer photo, contorting their backs so their heads and legs come together from behind. And they scream. It is such a surprising scream. We laughed so hard.) At 28—our first time setting up overnight camp so close to their burrows—I still think they’re magnificent.

Scout thinks they’re magnificent, too. Magnificently tempting. Magnificently taunting. Magnificently really-really-really-asking-to-be-chased.

This afternoon we’re exploring the area on a lazy walk. Scout runs ahead, snapping back to follow scent trails she almost missed, zig-zagging across the dirt, staying within social range but enjoying freedom of movement. She resists the urge to chase the prairie dogs, and it’s like I can see her brain working. She gets to make her own choices—to be “at liberty” rather than “under command”—in situations like these because we worked hard to teach her chasing isn’t allowed without permission.

Then one of the ferret-like bodies sprints in front of her. Right under her nose, two feet away.

And she takes off.

“Hey!” Sean calls out, raising his voice. It’s far from a mean shout, but it’s undoubtedly aversive to super-socially-sensitive Scout Finch. She stops the second the reprimand reaches her ears. She turns back and runs our way, chided but still enthusiastic: Her ears remain upright, her gait is as even as it ever gets, and she’s happy to ask for a treat from the bag she knows Sean keeps in his pocket.

Then we keep moving.

Scout continues running ahead, an adventurer. We continue following behind, her support crew. She checks in; we reassure her we’re still coming; she does not chase another prairie dog even as they squeak and dart and prance around us.

Technically, what just happened was this: Sean used positive punishment. In operant learning theory—the simple-but-sometimes-helpful basis for much of dog training—positive means to add a stimulus and punishment means to decrease a behavior. Sean added a verbal sound to decrease the odds of Scout chasing without permission again.

And it worked perfectly.

His level of response matched hers; it was not too subtle nor too intense for the situation. Scout understood what the “hey” was for. She did not become afraid of us or afraid of the walk or afraid of the prairie dogs. We just said “nope, don’t do that one thing” and left the door open for her to choose dozens of other behaviors. Our dog kept exploring. We all kept enjoying. And we immediately got to re-practice the same situation, which is a huge (and too often missed) part of discerning if our dogs are actually learning what we want them to.1

Instead of scolding Scout, we could have leashed her up. (We would have if this was earlier in our training journey. Keeping pets under responsible control around wildlife is a dealbreaker for me!) That would have been a perfectly fine way to prevent her from chasing without permission, but it also would have limited her freedom and fulfillment: The only leash we had with us was her four-foot slip, and she’s one of the many dogs who sniff more on longer tethers.

Or, instead of leashing her, we could have given her a command to follow. I might have asked her to finish the walk in heel position—maybe even “middle” between my legs—but again, she’d have lost the freedom to make her own choices. I’d be telling her one specific thing to do instead of one specific thing not to do.

In this situation and atop the foundation of our relationship—all these years we’ve spent working and growing and learning together—“punishing” Scout’s permission-less chase was the least invasive and most minimally aversive option. She experienced a couple seconds of discomfort when she realized we were disappointed in her. Then we all experienced another twenty-plus minutes of harmony moving through the world as a team.

One of my goals: Give my dog as much agency as possible within safe parameters.

I always feel worried talking about this (*gestures wildly*) and even more worried when I write about it, because you cannot see my facial expression and hear my tone. “Punishment” can feel like such a dirty word. And the more terrible dog training I see, the more I understand why. It is dirty sometimes.

We have to wade through semantics (do we mean “punishment” in a learning theory sense or colloquial way?) and previous associations (when I’ve just watched a compulsion trainer scare an already fearful dog in a bad training video, my tolerance for words like “punishment” goes way down) and then hopefully try to have a productive conversation.

Which brings me to my main point: Distilling everything we do with our dogs into operant conditioning quadrants is reductionist at best and harmful at worst. Yes, technically Sean “applied positive punishment” to “decrease an unwanted behavior” this morning. Sure, I guess. Except that doesn’t remotely feel like the best way to describe a natural interaction between social creatures. One being in a cooperative, trusting relationship said “don’t do that thing”—the other being said “oh yeah you’re right”—and then everybody kept on keeping on.

Another one of my goals: Remember not to treat my dog like a stimulus-response machine. She is not a human, of course, but she is also far from a robot.

We are, above all, a social team.

This is the kind of nerdy post I used to write a lot more frequently back in the days where “training Scout” was my entire personality. I appreciate you taking the time to read and think through it with me!

Other notes and news

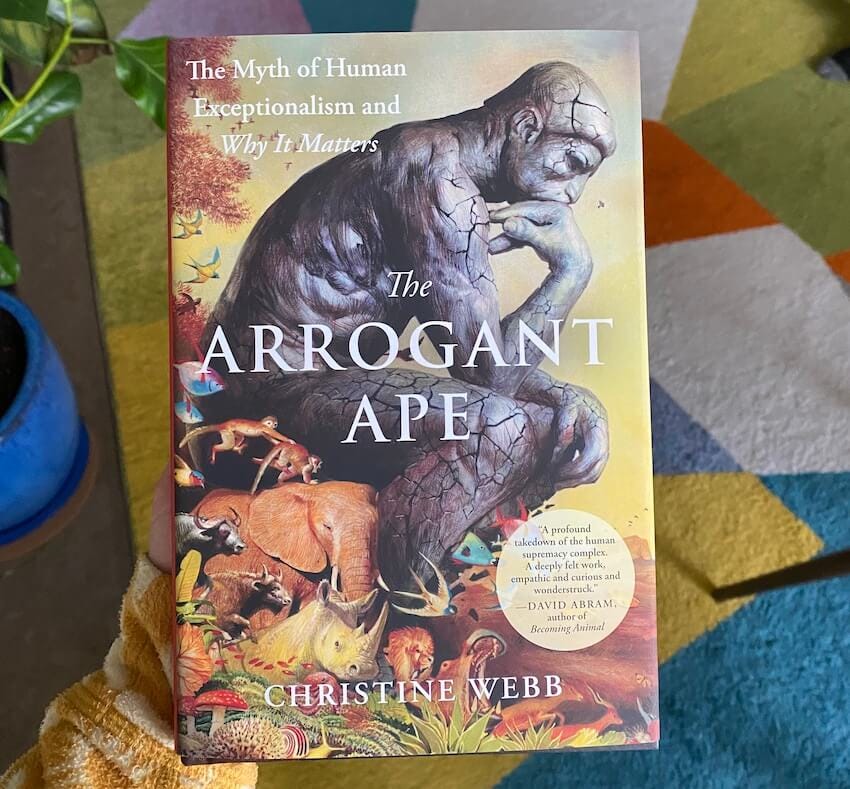

I picked up The Arrogant Ape by Christine Webb at Elliot Bay Books in Seattle this past weekend and could not be more euphoric that I did. (Remember: Buying hard-copy books is a big deal with the van’s super limited storage space!) The Arrogant Ape is exactly the broad, empathetic work I have wanted to exist in this world, eloquently arguing many of my own deeply held beliefs and introducing me to new connections I’d yet to see myself. I can’t wait to pass it along to friends and family members and fellow creature lovers, saying “here—this explains everything. This is how I feel.”

I also just missed seeing M.L. Rio, author of If We Were Villains and Graveyard Shift, in Seattle on tour to promote her newest book. (Cue sadness.) But I’ve got Hot Wax on queue and can’t wait to dive in soon!

Good Grief by E.B. Bartels comes out in paperback in less than a month! If you’ve read pretty much any of my recent posts here, you know that both E.B. and this particular work of hers have had quite the impact on me. If you’re able, please support her (and maybe gift the title to a friend to tell them they’re not alone in feeling so much for our pets).

In case you missed it

I took a photo of Scout in which I thought she looked suddenly very old, and so naturally I had to write about it. Read last week’s nuance-letter post here!

This is imperative: Sean’s “hey!” was not just an interrupter but actually a punisher. We had dozens more reps where prairie dogs again ran close to Scout, and she did not chase them. That is the goal of effective punishment. If my dog keeps doing the behavior I am trying to decrease—or if I feel the need to continue escalating and escalating and escalating into more intense displays of my displeasure—something is not working. (And the solution is not to just dial up my punishment attempts! That is where a lot of bad training lies. No, it’s to address the foundation of our relationship and build better baseline skills.)

I know there's a very good point here, and I think I even recognize it, but I have to admit that I'm mostly consumed with my own jealousy that other people's dogs can actually hear them when they're chasing prey. Which is hilariously ironic, seeing as how what I just said is ALSO, "I can't hear you because I'm thinking about myself!" Still, good job, Scout. Good job, Sean. I agree that there's a place for "hey, don't do that."

I named the dog Scout in my book, A Dog Named 647. This fictional dog was named after Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird.