What is talent without effort?

What is a title you do not earn? (Alternatively: I have been lazy.)

When I was a kid, I dreamed of becoming a marine biologist.1 I wanted to swim with dolphins and belugas and sea lions. I wanted to cooperate with—bond with—these fellow yet disparate creatures.

Here’s the other thing: I wanted to simply dream this career into existence.

My parents, confident I could be anything I wanted to be, encouraged me to pursue a range of interests. Perhaps they were too confident. I remember my mom once telling me that in order to truly work with marine mammals I’d have to swim and dive and hold my breath for long periods. Despite not being close to performing any of those skills, I brushed off her words. The work required sounded dull. It was effort I’d have to put in toward something that wasn’t even a guarantee—and I traded almost exclusively in guarantees.

I followed rubrics. I asked my teachers for feedback. I listened when they told me what to do. I liked living in the most predictable of worlds.

A few years after my beluga phase, I circled back to my dream of being an author. This is what I’ve answered, when you asked me what I wanted to be (which we all know really means who do you want to be), for the bulk of my life. On a middle-school spring bring in Florida I pointed to the gorgeous mansions across the river and brightly told my parents that when I was a rich author I’d buy them one. “You can have something too,” I added to my sister.

And unlike diving and holding-my-breath practice, writing was something I did. My first “real” piece of writing was a novel about a lost Siberian husky named Cyber finding his way home after a dog-hating neighbor dumped him in the forest. He accrued an entire pack of animal friends before returning to his owner, a young woman named Emma, who said of course these cats and other dogs and possibly a raccoon could now live with them! (This work was so heavily inspired by Erin Hunter’s Warriors saga that I can barely look it in the face nowadays. I made many, many mentions of bracken—small creatures and smells always lived in bracken—except I didn’t even know what bracken was. This is indeed the only note I recall my mother giving me about the book. “Maybe you should do some research about where the story takes place and what kind of plants and animals are found there.”)

For all its clumsiness, I loved that novel. I wrote a book, I thought. “I wrote a BOOK!!” I announced to anyone who would listen. Look at me, Haley Young the author, doing what writers did!

But not long after I finished Cyber in a blissfully offline bubble, I discovered immediate gratification. My sister’s best friend came over and saw me sitting in the big swivel chair in front of my family’s desktop computer. “Working on your book?!” she asked excitedly.

“Yes,” I lied.

In reality I was on Neopets messaging boards. I was discovering parts of the internet that allowed me to masquerade as creative and thoughtful without requiring me to do any real work to earn those adjectives.

And thus began a new pattern: I spent more time building my profiles on sites like Neopets and Tumblr than building my skills to actually write. (I would later be told to call this “personal branding” in the business school.)

At first there didn’t seem to be any problem. As a sophomore I got second place in a statewide writing competition with a piece I’d penned in an emotional rush over a year prior and barely edited for submission. People told me all my life that I was a good writer—that I was talented—and wasn’t this proof? I naively thought these things just came easily to me. And so, becoming a terrible cliche, I did not truly try. I walked around my high school’s lit mag meetings like I owned the damn place even though I hardly put in an ounce of effort. I wrote what felt good when it felt good. I rarely even ran into imposter syndrome: After all, writing was my thing. All the adults, all the time, told me it was my thing.

Why would I look for confirmation that it wasn’t?

For years and years and years this went okay because I wasn’t aware of what I was missing. Now I look back on the wasted time through tears. I can never reclaim my years of toddling about, I know, and yet I desperately wish I could. I want to scream (I sometimes do scream) about how selfish and foolish and complacent I was. It is lovely to believe you can be anything! But it is stupid to believe you can be anything without effort.

And then when I did start taking writing more seriously—when my account coordinator job turned into a content specialist role, when I left that agency to become a freelance copywriter, when not even a year ago I admitted I’d rather approach things from the journalistic or literary side than the marketing one—I had to face that my talent had somewhat shriveled from all those years of neglect.

I do worry (as these sentences pour out in an emotional rush not unlike the ones that preceded all my past writing) that I am not being fair to my younger self.2 I did love words. Occasionally I embraced a challenge. I’ve always kept some sort of blog, some sort of portfolio, some place where I can throw sentences out into the world. I have not pretended to write; I have written.

I was just too willing to lean into an identity I did not deserve. There was beauty in my eagerness—I love my freshman self in the rearview, so damn earnest, convinced she was profound—but there was ugliness in my attitude. I coasted on unexamined privilege atop a cushy foundation given to me by parents and teachers and friends in those formative years.

I thought I could just be. I did not realize I had to become.

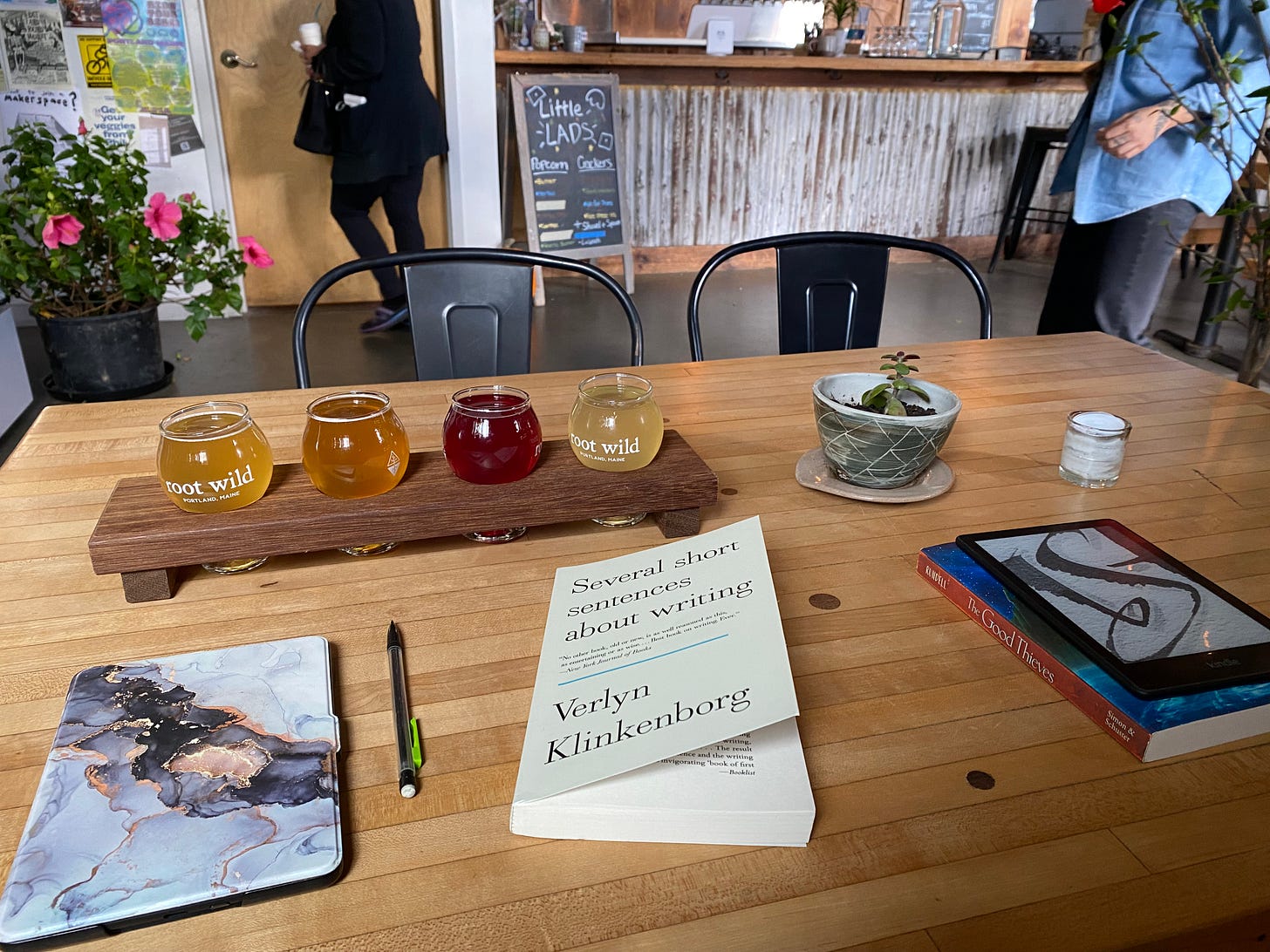

Becoming is what I want to do now. In the fall of 2023 I sat at a kombucha brewery in Portland, Maine, paging through Verlyn Klinkenborg’s Several Short Sentences About Writing, and I had as close to an epiphany as I think happens in the real world. I started taking client work more seriously. I started taking my own writing more seriously. That was the first moment “limiting” myself to a dog blog felt really not at all right.

A year and a half later I am proud of the work I’ve put in—but also still falling to old patterns. I spend more time talking about revising my book manuscript than actually working on it. I have occasionally whittled away a full hour of life (glorious life I could have been reading or revising or rolling on my back in the grass!) tweaking my Instagram bio and the About page copy on this blog. Then, hungover from shame, I wonder if this blog should even exist—as if that’s the most important question to ask myself.

I cannot keep shouting to the void that I am a writer without doing the work to actually be a writer.

I realized later how many of my peers shared this aspiration. If that’s you, hello, kindred spirits!

I’ve also overthought the nuances of calling myself a writer—of what it means to deserve that title—a bunch. My high school’s lit mag actually had shirts that said “#realwriter” on them specifically because our wonderful advisor wanted us to feel legitimate and did not want to perpetuate unproductive gatekeeping. I still stand behind that! But I think I, at certain points, took the internalization that I already was what I wanted to be too far—and it prevented me from learning and working and growing. Hence… this entire piece of journaling.